One of the central themes of Bataille’s philosophy that I encountered over the years is the notion of “the sacred” as a presence that was divided in two. Bataille doesn’t exactly use the terms “right sacred” and “left sacred” in his work, but one can easily detect the throughline of “the left sacred” in his work in any case, and Bataille is nothing if not an evangelist of the “left sacred”. The division of the sacred obviously recalls the division within modern occultism between the Right Hand Path and the Left Hand Path, whose terminology is itself derived from a similar divsion between Dakshinachara and Vamachara within Hindu Tantra. That being the case, one of my goals for studying Bataille was to understand exactly what “the left sacred” means.

Most of the information we need to understand Bataille’s notion of the left side of the sacred can be derived from Erotism: Death and Sensuality, but I find it would actually be better to start with Inner Experience instead. In Inner Experience, we find that Bataille actually does establish what we might take as a concept of “the left sacred” in connection to death and the animal world. Here Bataille seems to make the argument that knowledge of the self itself is intimately related with death.

Death is in one sense the common inevitable, but in another sense profound, inaccessible. The animal is unaware of death although it throws man back into animality. The ideal man embodying reason remains foreign to it: the animality of a god is essential ta its nature-at the same time dirty (malodorous) and sacred.

Disgust, feverish seduction become united, exasperated in death: it is no longer a question of banal annulment, but of the very point itself where eagerness runs up against extreme horror. The passion which commands so mkany frightful games or dreams is no less the desperate desire to be my self than that of no longer being anything.

ln the halo of death, and there alone, the self founds its empire; there the purety of a hopeless requirement comes to Iight; there the hope of the self-that-dies is realized (vertiginous hope, burning with fever, where-the Iimit of dream is pushed back.)

Georges Bataille, Inner Experience (page 71)

Bataille says that it is by dying that he will perceive the rupture that constitutes his own rupture and in which he transcends that which exists. As long as he lives, he is content with coming and going and with a compromise. A living being for Bataille knows itself to be a member of a species and existing in harmony with a common reality, but the self-that-dies abandons this harmony, perceives a void in its surroundings, and then perceives itself as a challenge to this void. Sovereignty is an important part of this knowledge. The self-that-dies is expected to arrive at a kind of sovereignty, and, even if it has not, it maintains a “harmony in ruins” with things in the arms of death. But without that sovereignty, it only challenges the world weakly, evasively, and while hiding something from itself. Death itself attains a contradictory significance for Bataille: death is commonly inevitable for all beings, but in another sense it is also profound and inaccessible. He claims that the animal is unaware of death, and yet death throughs humanity back into the animal world, and the man of reason is fundamentally foreign to death. It is here that Bataille also establishes a premise of the “left sacred”: animality is essential to the nature of Bataille’s notion of divinity, being both malodorous and sacred. The “left sacred” is the sacred that is also “dirty”, because it is also animal.

The purity of hopeless requirement is brought to light, and the hope of the self-that-dies is realised. In that sense, to challenge death or “die before you die” gains an altered significance. This significance may, arguably, be inseparable from the throughline we gleam from Carlo Michelstadter’s argument about persuasion and rhetoric. Bataille is in some ways talking about a kind of sovereignty that the self only achieves in death, and yet how will you know it when you die? Thus, one must “die before you die”, so that you may apprehend and grasp it at the climax of ritual descent, to render it accessible to yourself and the world, without dying. In the inaccessible death and the closed night there is no God anymore, for no one hears anything other than “Lamma Sabachtani” (more accurately “Eloi Eloi Lama Sabachthani”), the sentence charged with a sacred horror. In the dark void, there is chaos, but really a chaos that reveals the absence of chaos, because there everything is a desert, cold and nocturnal, but at the same time painfully brilliant and fever-inducing. The self grows until it reaches “the pure imperative”: “die like a dog”. This imperative has no use in the world that the self is turning away from, but in the distant possibility it responds to the demands of passion. A life devoted to death in this sense is like the passion between two lovers, and authority has nothing to do with it. Such is the eroticism of Bataillean mystic passion.

But, having digressed at this point, we should do continue to explore the notion of the sacredness that is also animal and impure, and to do this we had best return to Erotism.

It’s important to remember that eroticism, as Bataille understands it, is inherently religious, and so to discuss eroticism is inherently a practice of theology, or is at least closer to theology than to science. In fact, although Bataille feels he must shun them in pursuit of philosophical rigour and objectivity, he notes that there are many ideas found within occult or esoteric traditions which reflect a religious nostalgia relevant to the core of eroticism, and are thus inherently interesting. Conversely, Bataille claims that Christianity is actually the least religious of all religions, because it opposes eroticism and, by extension, opposes and condemns all other religions insofar as they possess the erotic element.

As far as the notion of a “left” sacred in opposition to a “right” sacred is concerned, we must focus on what Bataille observes to be element of division between “the profane world” and “the sacred world”, which figures into the discussion of taboo and death.

Primitive man as Levy-Bruhl describes him may have thought irrationally some of the time that a thing simultaneously is and is not, or that it can be what it is and something else at the same time. Reason did not dominate his entire thinking, but it did when it was a question of work. So much so that a primitive man could imagine, without formulating it, a world of work or reason to which another world of violence was opposed. Certainly death is like disorder in that it differs from the orderly arrangements of work. Primitive man may have thought that the ordering of work belonged to him, while the disorder of death was beyond him, making nonsense of his efforts. The movement of work, the operations of reason were of use to him, while disorder, the movement of violence, brought ruin on the very creature whom useful works serve. Man, identifying himself with work which reduced everything to order, thus cut himself off from violence which tended in the opposite direction.

Georges Bataille, Erotism: Death and Sensuality (page 45)

“Primitive” man was not completely dominated by reason, but its mind was encapsulated by work to the extent of imagining a world of work to which the world of violence is opposed. The world of work, or world of reason, is in this setting really “the profane world”, while the world of violence is called “the sacred world”. These are terms from “the vocabulary of irrationalism”, but they describe what Bataille interprets as expressions of great antiquity. The world of violence is in this discussion connected to death and disorder, and in this sense, violence, death, and disorder are united in the extent that they disrupt and destroy the order of work. The distinction between the world of work and the world of violence figures into the human experience of discontinuity and the salience of eroticism, in that identifying oneself with the world of work serves to identify oneself with order in general and thus cut oneself off from the world of violence that opposes it, and thus further solidifies our sense of socialised discontinuity. But violence and death also have a double meaning: on the one hand the horror of death repels us because we prefer life (which is a funny admission for a theorist of the death drive), but on the other hand something about it fascinates us, even if it also disturbs us.

Bataille sems to find a representation of this contradiction in the image of a corpse.

A man’s dead body must always have been a source of interest to those whose companion he was while he lived, and we must believe that as a victim of violence those nearest to him were careful to preserve him from further violence. Burial no doubt signified. from the earliest times, as far as those who buried the body were concerned, their wish to save the dead from the voracity of animals. But even if that wish had been the determining factor in the inauguration of this custom, we cannot say that it was the most important; awe of the dead in all likelihood predominated for a long time over the sentiments which a milder civilization developed. Death was a sign of violence brought into a world which it could destroy. Although motionless, the dead man had a part in the violence which had struck him down; anything which came too near him was threatened by the destruction which had brought him low.

Georges Bataille, Erotism: Death and Sensuality (page 46)

Throughout Bataille’s work, a corpse or cadaver is already figured as a symbol of an impure sacredness, the apophatic quality of the sacred, or the identity of divinity and impurity or excretory process. In his early works, Bataille spends some effort establishing the identity of the dead with the divine. We see an example of this identification in The Solar Anus:

The erection and the sun scandalize, in the same way as the cadaver and the darkness of cellars.

Vegetation is uniformly directed towards the sun; human beings, on the other hand, even though phalloid like trees, in opposition to the other animals, necessarily avert their eyes.

Human eyes tolerate neither sun, coitus, cadavers, nor obscurity , but with different reactions.

Georges Bataille, The Solar Anus

That which is sacred and also horrible and scandalous. The sun, perhaps, is an image of the left-sacred, even though it appears as a universal symbol of the dominant religious paradigms associated with the right-sacred. It can’t be ignored, though, that we cannot help averting our eyes to the sun even as it nourishes us and everything around us. Human eyes can no more tolerate sunlight than we can stand the sight of cadavers, obscurity, or perhaps even coitus. They are all in this sense inaccessible to us, at least normally. But the equivalence between the sun and the cadaver, and thus the larger theme of non-dualist identity between the sacred and the filthy, culminates in the broader equivalence of the sun and the anus, which is expressed in the link between the sun and volcanoes. For that reason the passions of scandal bear only one name: Jesuve.

In The Use Value of D. A. F. Sade, Bataille extends this sort of identification to the identity of God and Shit:

The notion of the (heterogeneous) foreign body permits one to note the elementary subjective identity between types of excrement (sperm, mentrual blood, urine, fecal matter) and everything that can be seen as sacred, divine, or marvelous: a half-decomposed cadaver fleeing through the night in a luminous shroud can be seen as characteristic of this unity.

Georges Bataille, The Use Value of D. A. F. Sade

As Bataille says in the accompanying footnote to this quote, the cadaver is not much more repugnant than shit, and the spectre that projects its horror is sacred. A passage from Frazer says that, in our eyes, different categories of people differ by their character and condition in that one group is “sacred” and the other is “impure” or “filthy”, but that the “savage” does not understand what the “pure” being and “impure” being are. Perhaps the “savage” view, “savage” according to Frazer at least, is the more profound one, at least insofar as we infer from it the non-dualism of the sacred and the impure. But it seems to relate to how Bataille describes De Sade as being treated as a “foreign body”, an object of the transport of exaltation to the extent that these transports facilitate his excrement, or more accurately a discussion of the identical attitude towards the divine and shit that relates to the stature of the “foreign object”. Thus, the identity of God and Shit.

The image of a cadaver wrapped in a luminous shroud, fleeing the night, as a symbolic representation of the unity of the gross and the divine, is an image perhaps equivalent to a black solar disc. It is clearly the image of impure sacredness. There is on the one hand a division between the sacred and the profane/filthy, which is defined ultimately as the division between supreme homogeneity and absolute heterogeneity, and the other hand a concept of a sacredness that is also profane, which is in turn thus entirely or fundamentally heterogeneous. The identity of the divine with shit and the dead, particularly the image of the half-decomposed cadaver fleeing the night in a luminous shroud, all form the clearest examples of that notion of the sacred. Another illustration of it is in the way that orgy, an excretory process, also allows its participants to incorporate heterogeneous elements to increase their mana.

The identity of gods and cadavers at first invites a comparison to Jesus, the son of the Christian God frequently worshipped in the image of a crucified (and often excruciated) cadaver. But we don’t think of Jesus as a cadaver, because of the doctrine of his resurrection and eternal sovereignty in Heaven, and the Christian cross itself is often represented without the cadaver of Jesus, thus the instrument of Jesus’ death is itself transmuted into a symbol of his divine authority, and thus the universal homogeneity to which Christianity is utterly dedicated as the cult of the One God Universe par excellence. But, if we remember Revolutionary Demonology, there is room to consider the right-sacred and the left-sacred, the Right Hand Path and the Left Hand Path, in terms of different angles of one single subject: the daily nocturnal voyage of Ra in Egyptian mythology.

Laura Tripaldi, in her essay “Catastrophic Astrology”, discusses Ra’s conflict with Apep as part of a larger discussion centring around the apocalyptic significance of the asteroid named 99942 Apophis. In this discussion, Tripaldi discusses the Egyptian magical treatment of Apep as the uncreation and unformed matter that must be violated and cut up in order to produce humanity and the order of the world and which must be continually violated dismembered in order to maintain the order of the world. In Egyptian mythology and art, that is represented by Ra, in the form of a great cat holding a knife, slaying Apep and chopping his body. If we grant Tripaldi’s account, this is no doubt a typical image of the Right Hand Path, or that of homogeneity: the great cat is in this setting an avatar or image of supreme homogeneity and its quest to degrade, diminish, or eliminate the heterogeneous elements, at least as long as it cannot capture and absorb them into homogeneity. But the Sun is also chthonic, it is also part of the underworld, and this brings us to the Left Hand Path. In Egyptian myth, when Ra journeyed through the underworld, he merged with Osiris, the god of the dead and the underworld, as part of a constant process of regeneration. This leads to the unified deity Ra-Osiris, whose “corpse” is Osiris and whose “soul” is Ra. “Corpse” is a fitting analogy in that Osiris is the god of the dead who was himself dead and reborn. Osiris himself was killed by Set, his body was dismembered, and then it was pieced back together by Isis with the help of the other gods. Osiris can, in a certain interpretation, be thought of as the lord of the underworld in the image of a revitalised cadaver. Thus, Ra, as the sun, identifies with just that might cadaver in the underworld. Ra in the underworld is in this sense a “black sun”, and not Apep as Laura Tripaldi would have it. Since this means the sun is also chthonic, identified with the dead and the god of the dead, then we are invited to consider something special about the left-sacred. The Left Hand Path, in this interpretation, is about eliminating the boundaries imposed by homogeneity, not establishing some balance between “light” and “darkness” but rather dissolving the dualistic boundary that demarcates the “superior” realm, so that the “inferior” realm – the demonic, the heterogeneous – may be acknowledged as a sacred object, one that is both sacred and profane, divine in a way that is also excretory rather than the sign of universal homogeneity and appropriation.

If Bataille is correct, what could be more heterogeneous than either shit or the dead? And Osiris, in Egyptian myth, is the lord of the dead who was himself dead. In this interpretation, the Right Hand Path is the great cat chopping a serpent into pieces to establish order, but the Right Hand Path is the “black sun”, the sun that is the underworld, Ra as Osiris and Osiris as Ra. And since Osiris was often identified by the Greeks with Dionysus, himself one of the supreme chthonic gods of Greek antiquity, this then connects further with the frenzy of Dionysus and therefore, in turn, with the frenzy of Sadean orgy. The Left Hand Path is the path of orgy, in that orgy is a source of great power and the destroyer of the boundaries of homogeneity.

But now to return to Erotism. The awe of the dead predominated the living for a long time, no doubt before the very emergence of civilisation and the sentiments that it developed. Death was often a sign of violence, brought into a world that can be destroyed by that violence. But according to Bataille the dead man often had his own part in the violence visited upon him, and anyone who approached him was threatened with the destruction that also killed him. The dead man in a sense represented a world so contrasted to and so unfamiliar with the everyday world of work that it necessarily conflicted with the world of work and the mode of thought that governed it. Symbolic and mythical thought was, according to Bataille, the only kind of thought appropriate for the violence that in itself breaks the bounds of rational thought that work implies. The violence that strikes the dead man and dislocates the ordered course of the world does not stop being dangerous after the death of the victim, but instead constitutes a supernatural danger that “catches” new victims, and is thus a danger to those left behind. Burial, for instance, is thus practiced less to preserve the dead and more to protect the living from the dead.

Moving on from corpses, though, we return to the figure of the animal as the other primary image of Bataille’s impure “left” sacredness within Erotism. Bataille says that the most ancient gods were generally animals, which made them immune to the taboos that fundamentally limit the sovereignty of humanity. Animals were regarded as sacred in a very specific sense: they were more god-like than human beings. This is probably connected to Bataille’s larger theme (possibly shared with Nietzsche) that animals lack the concept of the taboo, and in some ways co-operate with Nature more easily than humans. Killing an animal might have aroused a powerful feeling of sacrilege, and the act of animal sacrifice, if performed collectively, would consecrate the victim and confer divinity upon it. But the animal victim was already an object of superstition because of the curse laid upon violence, since animals according to Bataille never forsake heedless, being that it is the breath of their life. Of course, one might argue that animal violence is only strictly “heedless” from the human point of view, and the human being also finds itself trapped in the human point of view, thus almost unable to grasp the truth for as long as it remains there. From that very human point of view, animals knew “the law” and the fact that they violated it by acting accordance with their fundamental being, which is violence. In death, that violence reaches its climax in which they are wholly and unreservedly in its power: a divine manifestation of violence that elevates the victim above the world of work, order and reason, the world where humans live out their calculated lives.

As an animal, the victim was an object of superstition already because of the curse laid upon violence, for animals never forsake the heedless violence that is the very breath of their life. But as the first men saw it, animals must know the basic laws; they could not fail to be aware that the mainspring of their being, their violence, was a violation of that law: they broke it deliberately and consciously. But in death violence reaches its climax and in death they are wholly and unreservedly in its power. Such a divinely violent manifestation of violence elevates the victim above the humdrum world where men live out their calculated lives. Compared with these death and violence are a sort of delirium; they cannot stop at the limits traced by respect and custom which give human life its social pattern. To the primitive consciousness, death can only be the result of an offence, a failure to obey. Again, death turns the rightful order topsy-turvy.

Death puts the finishing touch to the sinfulness that characterises animals. It penetrates to the very depth of the animal’s being, and the bloody ritual reveals these secret depths.

Georges Bataille, Erotism: Death and Sensuality (pages 81-82)

“Primitive consciousness”, according to Bataille, views death as the result of some kind of offense or disobedience, and thus turns the world topsy-turvy. That specific point is interesting in that it actually seems closer to the narrative of human origin given within Judaism and Christianity. Adam and Eve, by eating the fruit of the tree of knowledge against God’s command not to do so, end up introducing death into the world, and when they are exiled out of Eden they become fully mortal: forced to toil for their own survival and ultimately destined to perish. In Christianity, all of this is blamed on Satan or The Devil, who thus in turn introduced death into the world by rebelling against God, and it is for this reason that Jesus called Satan “a murderer from the beginning” in John 8:44. Fraternitas Saturni connected the introduction of death to both rebellion and progressive human evolution through their myth that Lucifer introduced sex and death to the world by having sex with Eve: by doing so, Lucifer brought humans closer along the evolutionary path to becoming gods. In any case, from here Bataille says that death completes the “sinfulness” of animal life, penetrating the truth of its being, and the bloody ritual of animal sacrifice reveals its very depths. We might then consider an impure and transgressive form of sacredness and religion as one that is consciously linked to death in some way, and whose transgressive quality is linked to the disordering power of death and violence.

Bataille also returns asserts throughout Erotism that death implies the continuity of being, and it’s this premise that is central to Bataille’s discussion of transgression. According to Bataille, religion itself is the moving force behind the breaking of taboos. That much makes sense, when we understand religions themselves as being founded on numinous terror and awe. Humans must fight their urges towards violence, but that also signifies an acceptance of violence at the deepest level, and the urge to reject violence is so persistent that to accept violence lends to a dizzying swing, being seized by nausea and then by a heady vertigo. A sense of union with irresistible powers that bear all things before them is more acute in religions where one most deeply feels pangs of nausea and terror. Consciousness of the void about us throws us into exaltation, not because we feel an emptiness in ourselves but rather because we pass beyond that emptiness into an awareness of an act of transgression. But the question is, a transgression of what? The answer is this: the order of discontinuous beings. Divine continuity is linked to the transgression of exactly that order, which to an extent we must understand as the order of work, reason, law, custom, etc., the order on which the society of discontinuous beings is founded.

Here is where we come to something very interesting as regards the implications of left-sacredness. The dominant paradigm for our understanding of “the Left Hand Path” entails a strict emphasis on the cultivation of discrete individuality through ontological separation, but in Bataille’s view, transgression is actually linked to the destruction of discontinuous being as in the violation of our sense of separation, which is in turn linked to a return to the primordial continuity of existence. Taboo is a function that works to distinguish humans from other animals, in order to break apart from the dual world of sex and death in order to impose control through the order of work and reason. Transgression, however, draws humans back towards the animal kingdom, following how animals escape the rule of taboos and remain open to the violence or excess that reigns in the realms of death and sex or reproduction. Animal nature fundamentally opposes itself to taboo in that accord with animal nature makes it impossible to uphold taboo.

According to Bataille, there is some indication that animal nature was considered sacred in relation to the practice of sympathetic magic by “primitive” hunters, which implies both the observation of taboo and a limited practice of transgression. Once humans give rein to animal nature, they enter the world of transgression, and form synthesis between animal nature and humanity through the persistence of taboo. In so doing, we enter a sacred world, the world of holy things. Animal nature, to us, represents a world other than our own, and necessarily transgresses the world of work. But that transgression is also linked with a sense of the restoration of continuity: that is to say, the continuity of existence, represented by a world of sex, death, and violence. Perhaps the relationship between the animal and the human is the real link, in that the human “ego” separates us from the animal continuity that we cannot really extricate ourselves from. The human world, shaped by work and reason, is what denies animality and nature, and in so doing denies itself. In this specific sense, discontinuity could mean our attempt to establish discontinuity from the animal world, with humanity as a separate substance and identity from animality.

Of Bataille also clarifies in that breaking sexual taboos does not mean a return to nature in the sense we imagine of the animal world or in the sense of a “regression” to the animal kingdom, but the forbidden behaviour is like that of non-human animals, or so it seems. Human eroticism seems to begin where purely animal nature ends, but its foundation remains animal. We might turn from that foundation in horror, and yet we allow it to persist to some extent regardless. From this standpoint, eroticism can be seen as a vehicle through which we “rediscover” that animal foundation, to the effect that, even we do not “return to nature”, we transfigure and refigure humanity along its original foundation.

The spirit of transgression, according to Bataille, is a dying animal god; a god whose death sets violence into motion, and who untouched by the taboos restraining humanity.

The spirit of transgression is the animal god dying, the god whose death sets violence in motion, who remains untouched by the taboos restraining humanity. Taboos do not in fact concern either the real animal sphere or the field of animal myth; they do not concern all-powerful men whose human nature is concealed beneath an animal’s mask.

Georges Bataille, Erotism: Death and Sensuality (page 84)

The spirit of this world according to Bataille is the natural world mingled with the divine, which makes it seemingly impossible to grasp at first. Fortunately, however, we can easily grasp this as the world envision by pagan religions, both past and present. Paganism, and especially pagan animism, already views the natural world as being intimately intermingled and interconnected through the universal presence of divine spirits in the natural world.

Bataille observed that Christianity fails to understand transgression. Christianity, despite all appearance presented by radicals, is almost inherently opposed to breaking the law, and inherently allied to law as such.

The main difficulty is that Christianity finds law-breaking repugnant in general. True, the gospels encourage the breaking of laws adhered to by the letter when their spirit is absent. But then the law is broken because its validity is questioned, not in spite of its validity. Essentially in the idea of the sacrifice upon the Cross the very character of transgression has been altered. That sacrifice is a murder of course, and a bloody one. It is a transgression in the sense that it is of course a sin, and of all sins indeed the gravest. But in transgression as I have described it sin, if sin there is, and expiation, if expiation there is, are the consequence of a resolute and intentional act. The intentional nature of the act is what makes the primitive attitude hard for us to understand; our thinking is outraged. The idea of deliberately transgressing the law which seems holy makes us uneasy. But the sin of the crucifixion is disallowed by the priest celebrating the sacrifice of mass.

Georges Bataille, Erotism: Death and Sensuality (page 89)

Jesus himself insisted that he did not come to abolish the law but instead to fulfil it. In the Christian understanding, the law could only be broken when their “spirit” is absent, in other words when the laws of humans become invalid on religious grounds by going against the law of God. For this reason, the Christian mass and even the cross is never really identified with sacrifice, even if the death of Jesus can be understood the sacrifice of the son (Jesus) prepared by the father (God). In the crucifixion of Jesus, the character of transgression has been altered. It has nothing to do with the intentionality of the “primitive” act of sacrifice which outrages modern civilised peoples so much. The very idea of deliberately transgressing the law seems to disturb. Even though the church seems to sing “Felix Culpa” (“the happy fault”), as if to communicate an acceptance of the necessity of the deed, the apparent harmony with “primitive” religious thought strikes a false note in Christian in the logic of Christian religious sentiment.

It’s worth noting from here that Felix Culpa is also the name of a particular concept of Christian theodicy in which the Fall of Man is ultimately understood as having a positive outcome, in that it ultimately led to “redemption” through the incarnation of Jesus. This also comes with the view that for God to create or allow the existence of evil is better than for God to have never created or allowed evil on the grounds that from the evil that was created or allowed a much greater good and a new world of good would emerge. As Augustine himself put it, “God judged it better to bring good out of evil than not permit any evil to exist”. The same argument was also put forth by Thomas Aquinas to establish a causal relationship between original sin and the incarnation of Jesus Christ. There is a sense in which one might arrive at a utilitarian understanding of this argument, and all the manifold impermissible problems that come with that. But there may also be some paradoxical depth to it as well, one that gives way to something truly transgressive by accident. The idea behind the doctrine of Felix Culpa is that higher values or goods, indeed the highest ultimate value or good, ultimately emerges from the appearance or creation of evil. But there are many applications of this basic idea.

In fact, one immediately sees something of Ernst Schertel’s idea being harmonious with it: Satan is the beginning, Seraph is sort of the end, the chaotic potentiality of evil or the demonic is the basis of all higher forms of valuation. One can see something similar in Buddhism, or at least Japanese esoteric Buddhism, where the passions and the demons associate with them precede and in fact comprise enlightenment and buddha nature, for which reason the demon god Sanbo Kojin (identified with Mara himself) presents himself as the elder brother of the Buddha. There is a sense in which we can connect this to the way Bataille talks about sacrifice. Bataille understands sacrifice as a transgression, a violation of some law, but one that at the same time produces sacredness. Thus what we call “sin” is the engine of the production of the sacred, of religious value and truth, of all real holiness. The Left Hand Path, in this setting, might be understood as an active approach to the sacred defined exactly by impurity and transgression. It also lets us approach the Fall of Lucifer or the Fall of Satan on almost the same terms as Felix Culpa, at least in the exact sense that this fall at the heart of matter produces everything human, everything that transcends humanity, everything animal, and everything beautiful, holy, and immortal.

But Bataille also goes further: transgression is absolutely necessary to understand the link between sacrifice, love, and death. Without transgression, love and sacrifice have nothing in common.

If transgression is not fundamental then sacrifice and the act of love have nothing in common. If it is an intentional transgression sacrifice is a deliberate act whose purpose is a sudden change in the victim. The creature is put to death. Before that it was enclosed in its individual separateness and its existence was discontinuous, as I said in the Introduction. But this being is brought back by death into continuity with all being, to the absence of separate individualities. The act of violence that deprives the creature of its limited particularity and bestows on it the limitless, infinite nature of sacred things is with its profound logic an intentional one. It is intentional like the act of the man who lays bare, desires and wants to penetrate his victim.

Georges Bataille, Erotism: Death and Sensuality (page 90)

Sacrifice is a deliberate ritual act whose purpose is to create a sudden change in the victim. The creature, human or otherwise, is put to death, and this destroys the discontinuity of their being. The individual creature experiences life as a discontinuous entity, separated from the continuity of existence, to which it is “restored” in death. Violent death deprives the creature of its particularity and thus its limits, and in turn bestows upon it the limitless and infinite nature of the sacred. As is perhaps expected for Bataille the matter of sacrifice is also connected to sexual eroticism (which is also the subject of a previous Bataille-related article), much like the man who sexually penetrates his lover, or a woman who is sexually penetrated by her lover. The woman loses herself to or with her lover in a way not too distinct from the death of the sacrificed animal at the hands of the sacrificing priest.

Flesh is the element that brings transgression, love, sex, and death together.

Sacrifice replaces the ordered life of the animal with a blind convulsion of its organs. So also with the erotic convulsion; it gives free rein to extravagant organs whose blind activity goes on beyond the considered will of the lovers. Their considered will is followed by the animal activity of these swollen organs. They are animated by a violence outside the control of reasun, swollen to bursting point and suddenly the heart rejoices to yield to the breaking of the storm. The urges of the flesh pass all bounds in the absence of controlling will. Flesh is the extravagance within us set up against the law of decency. Flesh is the born enemy of people haunted by Christian taboos, but if as I believe an indefinite and general taboo does exist, opposed to sexual liberty in ways depending on the time and the place, the flesh signifies a return to this threatening freedom.

Georges Bataille, Erotism: Death and Sensuality (page 92)

Because of our modern distance from the world of sacrifice, we must try and imagine it. But one thing does not escape us: nausea. We have to imagine sacrifice beyond nausea, but, without the occurrence of divine transfiguration, different aspects of it recall nausea. When cattle are slaughtered or dismembered for consumption, the thought often disgusts us, even if we still consume their flesh as beef, yet almost nothing in modern life reminds of us this, except for maybe some vegan argument or activism. Bataille argues that this contemporary existence thus inverts both piety and sacrifice. But sacrifice itself is its own act of inversion, at least from a certain point of view, in that it replaces the ordered life of the animal with the blind convulsion of its organs. Both sacrifice and sex reveal the flesh. Just as sacrifice replaces animal and human life with a convulsion of organs, so does erotic convulsion give way to extravagant organs whose activity appears to go beyond the will of the lovers, which is followed by the purely animal activity of the organs. They are both animated by a kind of “violence” outside the control of reason, which is swollen to bursting point, and at some point the heart yields to it. Flesh is the thing whose urges pass through all boundaries in the absence of some kind of superego, it is itself that within us which finds itself opposed to the moral law we create, and it is the enemy of all who are haunted by Christian taboos. In a much larger sense, flesh represents the possibility of return to sexual liberty, and the threatening freedom it represents. If taboo exists as a repulsion of some kind of elemental violence, violence belongs to flesh, violence in the sense that denotes a wild, non-rational, extravagant, exuberant activity of the flesh that underwrites exactly what eroticism is.

There is in this sense a reason why there’s so much emphasis on sex in Satanism, and a lot of the Left Hand Path at large. Bataille is presenting a sacredness that has flesh and its violent power as its object. Although modern Satanism emphasises sexually in the sense of a liberation defined chiefly by progressive rhetoric, which challenges Christian morality on humanist and rationalist grounds, the force that Bataille is talking about must be acknowledged as something at odds with this very discourse, and which challenges Christian morality in a much more brutish way. Yet this flesh is the same flesh that has nearly always been the domain given to Satan, the adversary of the Christian God. Stanisław Przybyszewski was remarkably clear about what that meant, in that Satan was the father of the flesh, matter, and its passions and pleasures (as well as its agonies) and the Christian God was the enemy of all of that. Even while Przybyszewski tries to credit rationalist doctrines with the influence of Satan, at least to the extent that these undermined the Christian church, the core of what he presented Satanism to be has to be understood in terms of a non-rational (perhaps “irrational”), erotic, antinomian mysticism centred around the individual fulfilment of desires and wish and the magical cultivation of one’s own individualistic will alongside that. But with that connection in mind, whatever form of rationalist dogma passes for individualism in the modern memetic orthodoxy around Satanism simply doesn’t cut it. The cult of Satan is not just a gothic costume for atheists who devote their lives to rationalistic discourse. It is, properly speaking, antinomian eroticism and mysticism whose central subject is flesh, the kingdom of Satan or The Devil.

Even still Bataille goes further: Bataille suggests that transgression persists at the basis even of marriage.

Marriage in the first place is the framework of legitimate sensuality. “Thou shalt not perform the carnal act exccpt in matrimony alone.” In even the most puritan societies marriage is not questioned. But I have in mind the quality of transgression that persists at the very basis of marriage. This may seem a contradiction at first, but we must remember other cases of transgression entirely in keeping with the general sense of the law transgressed. Sacrifice particularly, is in essence, as we have seen, the ritual violation of a taboo; the whole process of religion entails the paradox of a rule regularly broken in certain circumstances. I take marriage to be a transgression then; this is a paradox, no doubt, but laws that allow an infringement and consider it legal are paradoxical. Hence just as killing is simultaneously forbidden and performed in sacrificial ritual, so the initial sexual act constituting marriage is a permitted violation.

Georges Bataille, Erotism: Death and Sensuality (page 109)

The whole process of religion entails the paradox a rule that is regularly and ritually broken. The initial sexual consummation of marriage is regarded similarly as the permitted and necessary violation of taboo. Bataille reckons there is always something “criminal” about the sexual act, especially when it involves virgins or when it takes place for the first time. Bataille claims that it was considered forbidden or dangerous, but that the lord or the priest were able to touch sacred things without risk to themselves. Forbidden, yet again, also means sacred, which means that, for Bataille, sex is sacred, and so is its criminality. But even so, transgression in marriage is transgression without consequence, and is nothing when compared to the orgy.

Ritual orgies allowed for an interruption of the taboo on sex, albeit a furtive one, especially when connected to feasts. The license was sometimes reserved only for some sort of fraternity, as Bataille claimed was the case for the “Dionysic Feasts”, but also had a religious connotation that Bataille says transcends eroticism.

In the orgy the celebration progresses with the overwhelming force that usually brushes all bonds aside. In itself the feast is a denial of the limits set on life by work, but the orgy turns everything upside-down. It is not by chance that the social order used to be turned topsy-turvy during the Saturnalia, the master serving the slave, the slave lolling on the master’s bed. These excesses derive their most acute significance from the ancient connection between sensual pleasure and religious exaltation. This is the direction given to eroticism by the orgy no matter what disorder was involved, making it transcend animal sexuality.

Georges Bataille, Erotism: Death and Sensuality (page 112)

Sexual frenzy itself has certain religious undertones:

One might just possibly consider the vogue of dirty jokes in our own day as having something of the marriage ceremony about it at a popular level, but this custom implies an inhibited eroticism turned into furtive sallies, sly allusions and humorous double meanings. Sexual frenzy though, with its religious overtones, is the true stuff of orgies. A very old aspect of eroticism is seen in the orgy. Orgiacal eroticism is by nature a dangerous excess whose explosive contagion is an indiscriminate threat to all sides of life. The original rites made the Maenads devour their own living infants in their ferocious frenzy. Later on this abomination was echoed in the bloody omophagia of kids first suckled by the Maenads.

Georges Bataille, Erotism: Death and Sensuality (page 113)

The link between sexuality and religious exaltation and overtones seems like an obviously prominent one for occultism, especially the Left Hand Path, and from this standpoint the orgy can be seen as the apogee of this. It’s no accident, then, that Satanism is so easily connected to theme of orgy not only in the imaginary of conspiracy theory as would make sense but also in the active mythology of Satanism or adjacent cultural phenomenon.

The world of the sacred is divided by work. It is work that establishes the distinction between the sacred world and the profane world, and is thus the origin of the taboos that alienate humanity from nature. But the limits of the world of work also defined the sacred world. In one sense, the sacred world according to Bataille is nothing but the natural world insofar as it cannot be reduced to the order of work and the labour of humans. And yet it is only the natural world in one sense. In another sense, it entirely transcends the world of work and its taboos. In this sense it is the world that denies the profane world, though owes its character to the very world it denies. Its significance is, according to Bataille, derived not in the immediate existence of nature but in the birth of a new order of things, which is brought about by the opposition of the world of work and productivity to nature. Work is what separates the sacred world from nature. In the sacred world, the explosive violence suppressed by taboo was regarded not just as an explosion but as an action, and thus something of use. These explosive instances consisted of war, sacrifice, and/or orgy, at least in that they were not originally calculated. But then, as transgressions, they became organised explosions, whose use value was secondary. Yet the effects of war were of the same order as the effects of work. The forces of sacrifice had consequences that were artificially attributed in the manner of tools. The orgy, though, was different. It was contagious. A man enters the dance because the dance makes him dance.

That Bataille goes on to refer to an explosive surge in transgression as being shaped by taboo would constitute a link to the earlier premise of the sacred world being defined by the profane world despite its opposition, but then this also implies a connection between the sacred world and violence, and at that explosive and orgiastic violence, wild and holy violence. Transgression too is implied to be violence. Here, again, there is an understanding of transgression that is linked to sacredness, as something that is at once sacred, both sacred and transgressive, blasphemous in a way that can only be divine and holy. Perhaps some aspect of that is linked to the way in which breaking the rules of the world of work is ultimately linked to the destruction of humanity’s own stifling isolation. Orgy plays an important role in this understanding in that it is in its excess against the world of work that the whole truth of that sacred world is revealed in its overwhelming force.

When discussing Christianity, Bataille makes plain that the divine is the essence of continuity and that continuity is reached through experience of the divine.

If Christianity had turned its back on the fundamental movement which gave rise to the spirit of transgression it would have lost its religious character entirely, in my opinion. However, the Christian spirit retains the essential core, finding it in continuity in the first place. Continuity is reached through experience of the divine. The divine is the essence of continuity. Christianity relies on it entirely, even as far as to neglect the means by which this continuity can be achieved, means which tradition has regulated in detail though without making their origin plain.

Georges Bataille, Erotism: Death and Sensuality (page 118)

This presents an interesting paradox that nonetheless opens itself up to a way of thinking about deification in the Left Hand Path in a different light. I wonder, if we combine Bataillean erotic philosophy with the “Neoplatonic” understanding of theurgy, maybe we might arrive at a way of understanding the rediscovery of continuity that is, at the same time, the creation of a new being, which is itself part of that continuity all the same, but in its own distinct way.

Bataille also provides another description of what he calls transgression: to make order out of what is essentially chaos.

The Christian God is a highly organised and individual entity springing from the most destructive of feelings, that of continuity. Continuity is reached when boundaries are crossed. But the most constant characteristic of the impulse I have called transgression is to make order out of what is essentially chaos. By introducing transcendence into an organised world, transgression becomes a principle of an organised disorder.

Georges Bataille, Erotism: Death and Sensuality (page 119)

The implication of this is that the organised world is an organised order whose destruction (theoretically) requires an organised presence of disorder, and the ability to disrupt or pervert this order constitutes the ability to generate one’s own order, either out of chaos or that is just as well chaos at least to someone or to oneself.

Christianity reduces religion to a certain benign salvific aspect while denying its dark side and projecting it onto the profane world. The Christian faithful are not made responsible for their sacrifice, and contribute to the Crucifixion only by their sins and failures, all of which shatters the unity of religion. In Paganism, according to Bataille, religion was based on transgression and the impure aspects of the sacred were no less divine than the opposite aspects. As Bataille repeatedly establishes throughout Erotism, the sacred consists of both purity and impurity. But Christianity rejected the impurity of the sacred. There is a guilt that must be in order for there to be sacredness, because it can only be revealed in the violation of taboo. Yet as much as “pure sacredness” has been dominant, “impure sacredness” has always lurked beneath the surface, and even Christianity could not get rid of impurity. Nonetheless, Christianity seems to have completely redefined the boundaries of the sacred world in its own image, in which impurity, uncleanliness, and what Bataille takes to be guilt were flatly excluded and thus confined to the business of the profane world, so that nothing that confessed the nature of sin or transgression would remain.

As I see it, some aspect of this process is no doubt reflected throughout our culture. It is absolutely the guiding logic of fascism in its quest to purify the body politic in its totality, excluding “degeneracy” and everything foreign and impure from the nation. It is also the inevitable driving force of consumer politics in its interaction in that the impure now takes the form of the problematic, which is more specifically the exuberance of eroticism and violence in media: the appearance of sex and violence (but most often sex scenes) in movies and TV shows are always questioned on the basis of their supposed necessity, which in turn is, as a critical device, nothing more than a mechanism of arbitrary moral exclusion. If there would be any reality to what we keep calling “cancel culture” or whatever new nonsense term we have for public disapproval of anything, it could nothing other than the process of the exclusion of impurity that Bataille attributes to Christianity. But all of this also takes us to a larger mainstay of Christian culture: the Devil, and more particularly the exclusion of the Devil.

The devil-angel or god of transgression (of disobedience and revolt)-was driven out of the world of the divine. Its origin was a divine one, but in the Christian order of things (which prolonged Judaic mythology) transgression was the basis not of his divinity but of his fall. rrhe devil had fallen from divine favour which he had possessed only to lose. He had not become profane, strictly speaking: he retained a supernatural character because of the sacred world he came from. But no effect was spared to deprive him of the consequences of his religious quality. The cult that no doubt still persisted, a survival from the days of impure divinities, was stamped out. Death by fire was in store for anyone who refused to obey and who found in sin a sacred power and a sense of the divine. Nothing could stop Satan from being divine, but this enduring truth was denied with the rigours of torment.

Georges Bataille, Erotism: Death and Sensuality (page 121)

Satan, or The Devil, is understood simply by Bataille as the angel or god of transgression, that is to say of disobedience or revolt. Already we get the picture that is already presented throughout modern Satanism and the romantic mythology that proliferated in the age of the Enlightenment, which is quite natural because the traditional Christian myth of Satan, and the attendant theodicies, all begin with his original revolt in Heaven against the rule of God. But even by this token, Satan should not be reduced to a mere icon of reason, even in his capacity as a patron of liberty. In any case, Satan was originally divine but later driven out of the world of the divine, and in Christianity transgression was the basis of Satan’s loss of divinity rather than his original divinity. He fell out of divine favour, and he seemed to possess that favour only to lose it. But Satan was not profane. Satan was still of the sacred world, even if he lives now in the profane world, and so he retains his sacred and supernatural character. But Christianity spared nothing to deprive Satan of the consequences of that sacred origin and his religious quality. Bataille implies the premise of a cult of Satan, as a remnant of older cults dedicated to impure deities similar to Satan, which was was stamped out. This cult seems to have been defined by the belief in the idea that sin holds a sacred power and a sense of the divine, which was punished by death. But, Bataille says (just as Przybyszewski did before him), nothing could stop Satan from being divine, even if that truth was denied by rigours of torment. All Christianity could do was portray ancient religion or Paganism as a criminal parody of religion.

There is something here worth focusing on: idea that sin holds a sacred power and a sense of the divine. At its core, is there anything more fundamental Satanism in a really religious sense? Satan is explicitly the patron of transgression, revolt, and thus sin, and therefore Satan is the embodiment of the sacred power and divinity of sin. There is a sense in which this is the truth of what I perceived a while back as Satanic negativity. Flesh aspires, transgresses, and in its own way negates in its exuberance. But more to the point, this idea that sin holds a sacred power and divine sense immediately brings us to a more concrete expression of the impure sacredness relevant to the Left Hand Path. It’s the idea that transgression, in the sense of sin, at least in the erotic sense, represents a link to the divine and a form of sacredness – not just in a “healthy” sense, not just for being approved in an official religious context, but precisely for its sinful, transgressive, and erotic import. That is the religious meaning that the Left Hand Path, and/or at least especially Satanism, has always concerned itself with, being part of the defining quality of both elements.

The impure world is also a central concern for Christianity, but in a strictly negative or opposing sense. For Christianity, the impure world was a form of profanation on its own, simply because of its existence, rather than strictly the notion of using sacred things for profane purposes. Meanwhile, the actual profane world was divided between the pure and impure worlds of the sacred: one side of the profane world allied with the pure sacredness, while the other side allied with the impure sacredness. Sanctity, which originally simply meant sacred things, became joined with the notion of Good and then at the same time specifically with God. But even then, the underlying affinity between sanctity and transgression has never stopped being felt, and, for Bataille, the libertine is much closer to real sainthood than a man who has no desires whatsoever. That idea has important implications. Meanwhile, the meaning of profanation is connected to what Bataille understands to be paganism. In “the heart of paganism”, contact with impurity was thought to result in uncleanliness (concepts such as the ancient Greek notion of miasma reflect that idea), and profanation was regarded as both unfortunate and deplorable.

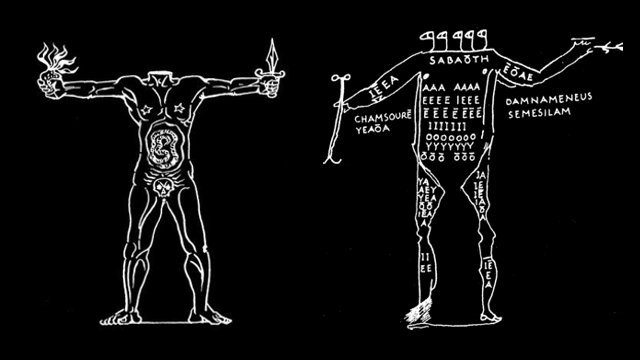

Transgression, meanwhile, is regarded as having the power to open doors to the sacred world, and to alone do that, despite its dangerous nature. This is an important consideration for Bataille, and it is central to the Bataillean understanding of the impure sacredness, as well as sacredness at large, and, by extension, eroticism as a whole. But it’s worth noting that, in antiquity, what we call magic tended to operate on such terms. The Greek Magical Papyri was essentially a collection of spells that would allow the magician to breach into the antechamber of death, or make contact with the underworld, and take on the powers and identities of the gods in a manner reflecting a kind of brief mystical union, in order to effect one’s own will into the world and fulfil one’s own desires or even achieve religious goals concerning unification with the divine. Funny enough, however, a huge portion of spells, if not the majority of them, concern erotic goals, such as the attraction of a woman or the separation of women from men. Magic itself is classically defined by sympathy, a force that attracts all sorts of objects and beings to each other, and perhaps, from a certain point of view, betrays a form of continuity, at least from the standpoint of “Neoplatonist” philosophers such as Iamblichus and/or Proclus. I would stress that magic is not at all irrelevant to this consideration, because Bataille later says in a footnote that magic is a left-handed or unclean religious phenomenon, and thus an expression of the left-hand side as described by Robert Hertz, which Bataille connects to the left and impure side of the sacred.

Christian profanation merely resembled transgression. Although Christian profanation gained access to the sacred and thus a forbidden world by way of contact with the impure, as far as the Christian church was concerned that very sacredness was both profane and diabolical. What the church regarded as “sacred” entailed something that was strictly separated from the profane world by the formal limits of what came to be called tradition. By contrast, the impure, the erotic, and the diabolical had no clear separation from the profane world, lacked a formal character to separate them, and no easily understood demarcation. Yet in the original world of transgression the impure was well-defined, with stable forms accentuated by traditional rites. In paganism, what was regarded as unclean was automatically regard as sacred at the same time. But since then, under the strictures of Christian sacred formalism, the unclean was condemned to become profane. The sacred uncleanness was merged with the profane in a way that seemed to contradict human memory and feeling about the true nature of things, but the religious structure of Christianity demanded it nonetheless. One of the effects of this is that it actually weakens the feeling of sacredness in the world, to the point that people seem to believe in the Devil less and less, or not at all, so that the already ill-defined dark side of religious mystery seems to lose all significance. The idea for Christianity, of course, is that the realm of religion would be completely reduced to the world of the God of Good (that is, the Christian God), whose limits are the limits of white light and on whose domain there is no curse.

Personally, I would argue that modern, mainstream, humanistic and atheistic expressions of Satanism have done this process no favours for Satanism at large. They are interested in the figure of Satan chiefly as the patron of their own humanistic values, in a sense inherited from some of the tradition of Enlightenment-era Romantic mythology. But they are often not at all interested in the dark side of religious mysteries, or the notion of sin as having any kind of sacredness, sacred power, or divine identity (to be fair, perhaps you can’t be too interested in that subject if you’re of the opinion that sin doesn’t exist or holds no merit as a subject), all of which has animated the entire notion of the cult of Satan since such a thing was ever imagined by anyone. The extension of humanist orthodoxy within Satanism has if anything served only to box that mystery out further, preserving it only as a confrontational aesthetic for some active atheism, progressive politics, or sometimes a particularly exuberant form of feminism. Of course, the older LaVeyan Satanism hasn’t been much better. Granted, the Church of Satan was relatively bold in its initial desire to actually form a religion, or rather a distinct church (remember that there was already Satanism before Anton LaVey), around Satan as the patron of carnal desire (and therefore the flesh), but in the beginning there was a certain ambiguity that made the most sense in Anton LaVey: on the one hand, apparently an atheist and expounding a religious ideology that he himself explicitly identified with humanism, but on the other hand clearly concerning Satanism with magic, ritual, ceremony, “dogma”, all the elements that make up religion, while connecting religion to the realm of flesh and sin or transgression, all even under the belief in discrete individuality that might survive death if one were to indulge enough in life. Yet, as subversive as this might have been, LaVeyan Satanism nowadays tends to function, in much of its believers, as essentially an aesthetic for some sort of elitist right-wing politics, best understood as a generalised ideology comprised of a blend of Randian Objectivism and fascism, centred ultimately on the concept of eugenics and the creation of a eugenicist social order. The Church of Satan still holds its religious observances, it keeps up the memory of what Anton LaVey sought to create, and it aggressively asserts that its doctrine of Satanism is the only real one, and that all other Satanists are really Christians. But the Church of Satan also really treats itself as a corporation, one that mostly just exists to promote the eugenicist and somewhat eclectic right-wing fascist ideology of its members, and LaVeyan Satanism, as it exists today, functions mostly as an aesthetic for this corporation and the ideology it exists to promote.

The theme of the so-called “Witches Sabbath” is also given attention by Bataille’s analysis, and here we once again come to a concrete expression of a transgressive and impure sacredness. The subject of the Witches Sabbaths is explicitly connected to the orgy, to the effect that we might even almost treat the name Witches Sabbath as simply a medieval name for the phenomenon of ritual orgy. The subject of the Witches Sabbaths is explicitly connected to the orgy, to the effect that we might even almost treat the name Witches Sabbath as simply a medieval name for the phenomenon of ritual orgy. Orgy emphasized the sacred nature of eroticism, allegedly transcending individual pleasure, and this caught the attention of the Christian church. The church opposed eroticism by treating it in terms of profane sex outside marriage, and the feelings roused by the transgression of that taboo had to be suppressed at all costs. But the church’s struggle was difficult, for a religious world without uncleanliness was not readily accepted. Bataille suggests the existence of nocturnal celebrations in the religious world of the Middle Ages or the beginnings of early modernity, but if they exist, we know nothing about them. The problem, of course, is that Witches Sabbaths as actual historical phenomenon fall under what scholars call the elaborated theory of witchcraft, which posits an organised conspiracy of devil worship that gathered to practice human sacrifice with the aim of overthrowing Christianity, and in this regard, no evidence has ever been found to suggest the existence of anything that would fall under that. Of course, the suggestion is this has something to do with the systematic regime of repression and torture that the church employed, but even then, if there were any real evidence of any conspiratorial cult of devil worship, the church would not have hesitated one bit to parade it before the world, as they are never shy to announce the existence of heresy, real or imagined, and it would constitute, in the minds of Christians, proof of the apocalyptic war they believe is being waged against God.

Still Bataille supposes that there was a limit to Christian vigilance and that there were cults that consisted of the remnants of pagan festivals, celebrated in the deserted moorlands on the basis of a half-Christian mythology and a theology that substituted Satan for an older set of pre-Christian deities. Bataille says that it is not ridiculous to suggest that Satan in this setting is a kind of revival of Dionysus, a theme that he discussed in the essay Dionysos Redivivus (he actually uses those words at the end of that paragraph too!).

We’ can only suppose that Christian vigilance could not prevent the survival of pagan festivals, at least in regions of deserted moorlands. We may well imagine a half-Christian mythology inspired by theology substituting Satan for the divinities worshipped by the yokels of the high Middle Ages. It is not even ridiculous at a pinch to see the devil as a Dionysos redivivus.

Georges Bataille, Erotism: Death and Sensuality (page 125)

Indeed, Bataille appears to be convinced that the Witches Sabbath is real, and that Joris Karl Huysmans’ depiction of the Black Mass in his novel La-Bas is fundamentally authentic. That being the case, what does Bataille derive from the Witches Sabbath and the Black Mass?

The Witches Sabbaths were dedicated to a secret cult to a god who was “the other face of God”. That could be understood as Satan or the Devil. They also entailed a ritual based on the topsy-turvydom of the feast, and are therefore an intimate and explicit expression of sacredness. Sacrilege was the basic principle. The Black Mass was the name given to the meaning of the infernal feasts, which entailed a parody of Christian or specifically Catholic feasts and rites. The Witches Sabbaths describe an unleashing of passions that is implied and/or contained in Christianity. In pre-Christian religions, transgression was relatively lawful, ironically enough, piety demanded it. Transgression was opposed by taboo, but taboo could be suspended temporarily in the context of ritual feasts and orgies, and within the observed limits of these celebrations. But in Christianity, the world of taboo is absolute. Transgression would make clear what Christianity concealed, which is that the sacred and the forbidden are actually the same and that the sacred can be reached through the violence of a broken taboo. In Christianity, accessing the sacred is evil, and at the same time evil is profane. Yet being evil, being free, and existing freely in evil, was not only the condemnation but also the reward of the guilty and the sinful, at least since the profane world is not subject to any of the restraints of the sacred world. For the Christian faithful, license and excessive pleasure condemned the licentious and showed up their corruption. But for the sinner, or for the worshipper of the Black Mass, corruption, evil, and therefore Satan or The Devil, were objects of reverence, adoration, and/or worship. Pleasure, being plunged into evil, was essentially a transgression that transcended horror. And the greater the horror, the deeper the joy. Whether real or not, they are the dream of monstrous joy. The work of Marquis De Sade seems to expand that world up to the enormous possibility of profanation and profane liberty.

It seems to me that this monstrous joy is, within Christian culture, an expression of the exuberance of sacredness, and therefore of the erotic and/or impure sacred world. It is just this world that Satanism, and the Left Hand Path, concern themselves with. But, implicitly, it’s also an approach to sacredness that requires a different approach to evil and sin, one that does not follow Christian morality without necessarily boxing out the category that gives transgression the meaning that Bataille implies. Evil is not transgression per se, rather it is transgression condemned. Evil is sin. But what is sin if not transgression? Bataille says that sin is what Charles Baudelaire means. Charles Baudelaire wrote in Mon cœur mis à nu that the unique and supreme pleasure of love is based on the certainty of doing evil, and that everyone knows from birth that all pleasure is to be found in evil. But then so far, as far as Bataille is concerned, evil exists as simply the condemned status of transgression. I’m not sure I believe that a clear separation between these concepts is possible, if we remember that the concept of sin is, in its traditional context, understood simply as disobedience, acting against the commands of God. But then, folks, that means we are intending to take from Bataille a way of illuminating the real depth of disobedience, and truly grasp the Key of Joy. As Crowley said, the key of joy is disobedience.

Sacredness, for Bataille, is something that dominates or subdues shame. The religious and sacred nature of eroticism has, in ancient times, been shown in the full light of day. An almost predictable example is given by Bataille in the form of numerous Indian temples still covered in erotic imagery, carved in stone upon the sacred edifice, thus communicating that eroticism itself is entirely divine. This, Bataille says, reminds us of the obscenity laid deep in our hearts.

We must not forget, however, that outside of Christianity the religious and sacred nature of eroticism is shown in the full light of day, sacredness dominating shame. The temples of India still abound in erotic pictures carved in stone in which eroticism is seen for what it is, fundamentally divine. Numerous Indian temples solemnly remind us of the obscenity buried deep in our hearts.

Georges Bataille, Erotism: Death and Sensuality (page 134)

No doubt Bataille is referring to places such as the Khajuraho monuments or temples, which actually only contained a small amount of erotic imagery, perhaps comprising around 10% of the entire complex. Still, there is certainly a significance to the erotic imagery. It has been suggested by scholars that the erotic images at Khajuraho reflected the influence of Tantric Hindu teachings such as conveyed in the Agamas, or were meant to convey kama (sex or sexual desire) as an essential, natural, and proper part of human life, or that the images of a man and woman in sexual embrace (or maithuna, which in Hindu Tantra is one of the Panchamakara or “Five M’s”) are themselves symbols of the Hindu concept of moksha (liberation from the cycle of death and rebirth), and the final reunion of the two principles of purusha (cosmic awareness or selfhood) and prakriti (matter). Now here is a clear link between eroticism and continuity: through sexual union, the discontinuity of two beings, and two principles, is overcome through sexual union, through eroticism, and between them the continuity of being is discovered and established. Another famous example of erotic religious architecture would be the Konark Sun Temple, dedicated to the sun god Surya. The temple’s shikhara (rising tower) contains multiple erotic depictions of couples engaged in maithuna, which, despite a lack of evidence, was believed to reflect the practice of Vamachara Tantra, since maithuna was one of the Panchamakara practiced in Vamachara Tantra.

Erotic sculptures also appear in multiple Hindu temples besides just the many temples in Khajuraho and the sun temple in Konark. These include the Virupaksha Temple in Hampi, the Bhoramdeo Temple in Kawardha, the Modhera Sun Temple, the Sathyamurthi Perumal Temple in Thirumayam, the Kailasa Temple at the Ellora Caves, the Lingaraj Temple in Bhubaneswar, the Markandeshwar Mahadev Temple in Sakhari, the Garhi Padhavali Temple in Morena, the Nanda Devi Temple in Almora, the Tripurantaka Temple in Balligavi, among probably several others. All of this would most likely support the view that the sculptures simply reflect the sacred place of sexual intercourse in Hindu life, moreso than the specific practice of Vamachara Tantra. There are also Jain temples in Ranakpur and Osian (The Mahavira Jain Temple) which both feature erotic maithuna depictions, which may suggest a place for it within Jainism. The point, of course, is that, within the broad context of Indian religious culture, eroticism and sexual intercourse did have a sacred value, and a very explicit and open one, just as Bataille said. In Hinduism, this is reflected in the role of kama in the practical and religious life of the practicing Hindu. In contrast, the mainstream of Buddhism considers kama to be a hindrance to enlightenment. At the same time, some forms of Hindu theology also consider kama to be a spiritual opponent that hinders the attainment of moksha. Kama is also the name of one of the millions of deities worshipped in Hinduism, and he of course is the deity of erotic love, desire, and pleasure.

As an incidental note, the discussion of Indian temples leads us to a broader consideration of the parallel with Hindu Tantra. The Panchamakara system presents a clear connection to the transgressive aspect of the sacred. The Panchamakara represent taboos within Hindu religious practice or more specifically Tantra: drinking alcohol (madya), eating meat (mamsa), eating fish (matsya), eating grain (mudra), and sexual intercourse (maithuna). In Dakshinachara (Right Hand Path) Tantra these were strictly symbolic representations of certain mental and spiritual states, while in Vamachara (Left Hand Path) Tantra they were literally practiced. The practice of Panchamakara within Vamachara Tantra entailed breaking religious and social taboos so as to achieve spiritual transformation on the path to God-realisation. This, of course, is transgression, the violation of the taboo, opening the sacred world, and it is a practice that explicitly acknowledges and supports a link between sacredness and transgression. The “obscenity laid deep in our hearts” is no doubt reflected in Hindu Tantra through the symbolism I have already discussed in relation to the Tantric Hindu goddess Chinnamasta: her self-decapitation and rampant sexuality all link to the idea of nature as system based on sex and death, where life derives from life, and thus from death, and depends on sexual intercourse, all in order to perpetuate, decay, and reproduce indefinitely. That reality, dark and barely comprehensible, is the “obscenity” in our hearts. That is what the Left Hand Path, within Hindu Tantra, is focused on, and that is reflected even in the most extreme sects such as the Aghori: God-realisation involves an intimate familiarity with just such a reality, and that involves breaking the taboo of the discontinuous order of being.

Once again, let us look to the subject of animal nature, and Christianity morality concerning animal nature:

Looked at as a whole, the transition from a purely religious society (and I connect the principle of transgression with the state of society) to the times when morality gradually established itself and gained predominance is a very difficult problem. It varies from country to country in the civilised world, and the victory of morality and the sovereignty of taboos were not everywhere as clearcut as with ChristianIty. Nevertheless I think there is a perceptible link between the importance of morality and contempt for animals: contempt implies that man thinks he has a moral value that animals do not possess and which raises him far above them. In so far as “God made man in his own image”, man had the monopoly of morality as opposed to inferior creatures and the attributes of deity vanished from the animal kingdom.

Georges Bataille, Erotism: Death and Sensuality (page 136)

Previously we have discussed animal nature as being aligned with transgression in that it operates outside of, and is opposed to, the taboo of the human world, and that transgression is very much allied with animal nature and the violence of the animal world. Christianity, as we have also previously discussed, completely excludes any notion of impurity or transgression, anything “impure” or “horrible”, from its conception of the sacred world, and alliance with the animal world is among the most obvious characteristics of the world of transgression. Christianity intends to present the victory of morality and sovereignty of taboo over impurity, transgression, and sin (and hence death), and to be sure such an idea is almost nowhere more clearly pronounced other than in Christianity. That morality implies a degree of contempt for the animal world, both externally and in ourselves, based on the idea that the human species possesses a unique moral value that the rest of the animal kingdom does not and which thus elevates humanity far above the other animals. God “made Man in his own image”, so humanity assumed a monopoly of morality as opposed to the other animals.

This conceit is everywhere in human civilisation, even in vegan movements that oppose the consumption of animals, and is anything all the more pronounced in transhumanism and especially certain transhumanist ideas about “herbivorizing” carnivorous animals. More importantly, one of the main religious effects of this is that, with a few exceptions (such as maybe the veneration of St. Christopher as a dog-headed man, though this practice is not supported by the Orthodox Church), the attribute of divinity was denied from the non-human animals. Tellingly, it is only Satan, or The Devil, Lucifer, and the whole infernal Pandemonium (that is, the entire kingdom of demons) that remained part beast, with his tail the first sign of transgression. The beastlike attributes of The Devil and the demons also connected them to various pre-Christian pagan gods, such as Bes, Pan, or Silvanus. That theme ultimately culminates in the figure of the goat-headed Baphomet, whom Eliphas Levi identified with Pan, and the inverted pentagram featuring the head of the goat, representing Satan, or the goat of lust that assaults heaven with its horns.