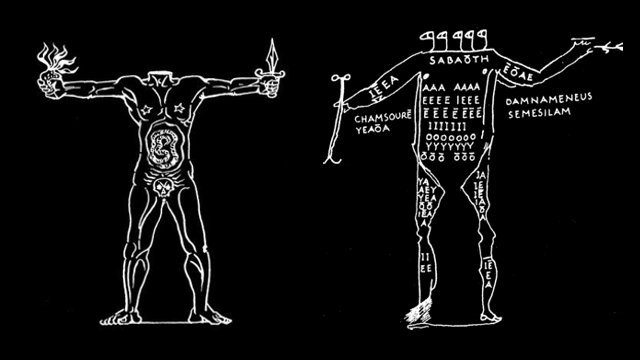

Probably the most prominent symbol associated with the philosophy and mysticism of Georges Bataille is the image of the Acephalic Man, or rather the headless figure that appears on the cover of the first issue of Bataille’s Acephale journal, and also in illustrations throughout all volumes of Acephale. Designed by Andre Masson in 1936, it is a rather delightfully esoteric image that suitably conveys Bataille’s particular brand of Nietzschean anti-fascism, with its Dionysian subversion of the image of human reason in the form of the Vitruvian Man without a head. However, what motivates this article is a question that I’ve seen from Pagans and occultniks who appreciate Bataille’s writings: does Bataille’s Acephalic Man have anything to do with the Headless One invoked in the Greek Magical Papyri? My aim here is to try and answer that question.

But, before we proceed, let’s briefly describe the Headless One that we’re talking about. The Headless One (a.k.a. the Headless God, or the Headless Demon, or Akephalos) is an enigmatic deity, daimon, or demonic figure (depending on who you ask, at least) who occasionally appears in multiple spells, most notably the Stele of Jeu the Hieroglyphist in His Letter (PGM V. 96-172). The Stele of Jeu in particular is perhaps most remembered for having been popularised by Aleister Crowley, who adapted the original spell into what he called the Ritual to the Bornless One. The Headless God seems to be very obscure by ancient standards, though according to Hans Dieter Betz he seems to have originated in ancient Egypt and was later popularly invoked in Hellenistic Egypt. Scholars aren’t entirely sure about the Headless One’s identity, thoug Betz suggests that he could have been identified with the god Osiris. But, we’ll get into the Headless One’s identity in due course.

With that established, let’s focus on what the Acephalic Man that appears on the cover of Acephale meant for Georges Bataille. And, in this respect, there is nowhere better to turn to than The Sacred Conspiracy (or, The Sacred Conjuration), which was written in 1936 as the first article for the first volume of Acephale.

What’s important to note about this particular text, and what I admire most about it, is that it is nothing less than a bold declaration of war. It could be seen as an essay concerned with political agitation, but in this regard it takes said agitation as strict necessity, of the same type as eating and producing, which are necessary and yet still nothing. In many ways, The Sacred Conspiracy might in fact be seen as an anti-political vision: “If nothing can be found beyond political activity, human avidity will meet nothing but a void”. In other words, if life consists of nothing other than political activity, in the sense of the necessary business of politics, then there is not only nothing in life but also no interest in life in itself, and there is nothing to life. Spare a thought for the bleak life of democracy. But Acephale is also “ferociously religious”, and insofar as your existence is a condemnation of everything that is today, an inner exigency demands equal imperiousness, because Acephale is starting a war: a war against the “civilised” world and its light.

In this respect, the headlessness of Bataille’s Acephalic Man signifies, first of all, the yearning to break free from the necessity of the civilised world and the magic circle of appropriation (what Claudio Kulesko calls the Image of the World) that supports it. Human life is fatigued and exhausted from its own conceit as the head of or reason for the universe. Humanity has taken up the mantle of cosmic reason and Logos for itself, and as a result human beings have accepted servitude, under the belief in its necessity. This existence becomes empty over time. Without it, the universe is free, and when the universe is free it is in play. This idea can be seen as a reflection of the Nietzschean cosmos, through the conception of the universe as a child in play. The universe was free when it just gave rise to cataclysms, trees, and birds: in other words, all the spontaneous life forms, powers, and flows that comprise much of what we call nature. That freedom was lost when the Earth gave birth to human beings, who demanded the establishment of necessity as a law above the universe. But human beings are still free to reject or rebuff that necessity, to set aside the idea that Man or God keeps life and the universe from collapsing into absurdity, and therefore renounce the whole mantle of cosmic Logos that we created and took for ourselves. Man is also free to resemble everything in the universe that is not Man. The headlessness of the Acephalic Man is that freedom: “Man has escaped from his head just as the condemned man has escaped from his prison”.

Man finds beyond himself something that is not God, “the prohibition against crime”, but instead a being who is unaware of prohibition. The Acephalic Man is both beyond and unaware of prohibition. God, in this parlance, seems to simply denote the concept of prohibition, possibly also necessarily being an ontological embodiment of law and authority in itself. The Acephalic Man, by contrast, is made of innocence and crime. He holds a knife made of steel in his left hand, and flames like the sacred heart in his right hand. To the untrained observer of the occult this would almost recall the left side of the Tree of Life being Binah, severity, and the right side being Chokmah, mercy. The Acephalic Man reunites Life and Death in the same eruption. This is to say the Acephalic Man represents the real spontaneous unity or intimacy of life and death. The Headless One is not a man, and nor is he a god. The Acephalic Man is “me”, but more than “me”. It is as if the Acephalic Man represents something that one can become, by casting off the self-imposed responsibilities of Logos and Godhead, and the necessity around it. His stomach is the labyrinth in which he loses himself and the person along with him, and in which “I discover myself” as him: “in other words, a monster”. So the Acephalic Man is a monster, and the labyrinth, perhaps, is the path in which we become more than we are, more than human, and become “monsters”, thus achieving our own liberation from the civilised world and its light.

It is very easy to make the connection from this theme of monstrosity to Eugene Thacker’s idea of the monster as representing “unlawful life”, that life which cannot be controlled, and from there through Alejandro de Acosta’s envisioning of anarchy as the art of becoming monstrous and intangibly weird in Green Nihilism or Cosmic Pessimism. There is a certain axiom, “I may be a monster but I am free”, that I would like to explore further, especially in relation to Shin Megami Tensei and other media, in the future. But in this sense, it seems that Bataille’s Acephalic Man as a monster presents a glimpse of the kind of throughline relevant to that inquiry of anarchy.

The Acephalic Man in The Sacred Conspiracy can be seen as representing a universe unmanned and the human being equally unmanned. It is the apotheosis of a universe without reason and without law, of the entirely free universe of incomprehensible spontaneous forces. Ecstasy, or the ecstatic vision of life, is central to this in that it is that very process of unmanning, in that “to go outside oneself” really means to go outside the human and its authority, and beyond that of this world: in other words, to step outside “the head”. “Man” steps beyond God, and “the head”, and sees something more than “Man”. I choose to see the “monster” as what “Man” could be, or realise itself to be, once it has cut itself free from “the head”, as in the Godhead or the OGU (the One God Universe; thus the monotheistically ordered homogeneity of everything).

Bataille also elaborates on the meaning of his Acephalic Man in Propositions, an essay that was written for the second volume of Acephale. Here, Bataille spells out that the Acephalic Man is a representation of the Nietzschean Ubermensch, which is in itself identical to the Death of God.

The acephalic man mythologically expresses sovereignty committed to destruction and the death of God, and in this the identification with the headless man merges and melds with the identification with the superhuman, which IS entirely “the death of God.”

For Bataille, the Nietzschean Ubermensch and the Acephalic Man are bound together by a shared significance: time as the imperative object and explosive liberty of life. In this setting, time appears as the object of ecstasy and a symbolic representation of the Nietzschean concept of eternal return, but also as catastrophe or time-explosion. This ecstatic notion of time is represented by things of “puerile chance”: cadavers (and hence death), nudity, explosions, spilled blood (thus bloodshed), abysses, sunbursts, and thunder. It is very fitting that the Acephalic Man is represented as a monster, because the emergence of the monster is a lot like catastrophe. Catastrophe is also important as the “brute appearance” of revolution, and the only “real” imposing authority. Thus the Acephalic Man seems linked to the intimacy of violence and politics, which in turn is an emanation of the intimacy of life and death. God and the tranquility he offers to humans is a barrier between the human species and the universal community of the infinite and of a universal existence that is uneasy, unfinished, and headless. The Death of God is thus, for Bataille, the true universality of life, and the Acephalic Man symbolically represents that.

Having established this about the Bataillean Acephalic Man, we should now start exploring the Akephalos as it appears in antiquity, and in this regard, I think we should immediately turn our focus to the Greek Magical Papyri.

The Greek Magical Papyri contains multiple spells that involve the invocation of a Headless God, whose identity is somewhat mysterious but at the same most likely connected to Osiris, the Egyptian lord of the underworld. The most famous myth about Osiris is that he was killed and dismembered by his brother, the god Set. Most spells featuring the Headless One feature a direct link to Osiris, though they also explicitly identify this god as Besas (Bes). In the Stele of Jeu the Hieroglyphist in His Letter (PGM V. 96-172), the Headless One is referred to by name as Osoronnophris, a form of Osiris, but is also referred to as Iabas and Iapos and identified with YHWH as the god who transmitted the mysteries celebrated in Israel. In PGM VII. 222-49, the Headless One goes by the name Besas, but is also conjured by the name Anouth, apparently another name for Osiris.

Jake Stratton Kent considers the Headless God to be representative of a solar-pantheistic cult that he sees as being referenced in multiple PGM spells – particularly in the spells centering on the gods Helios, Abrasax, and Typhon-Seth. In his study of the Ritual to the Bornless One, which originated as the Stele of Jeu the Hieroglyphist in his Letter, he notes that there has been a fashion in modern occultism, starting with either Mathers or Crowley, to interpret the word “headless” as meaning “without beginning”, thus was derived the name “Bornless One”. This was based on an assumption that, since the Hebrew word “Resh” means “head” or “beginning”, “headless” must mean “thou who are without beginning – unborn and undying”. Kent notes, however, that this interpretation cannot be sustained by the knowledge derived from contemporary study of the Papyri, and it is already evident that this interpretation derives strictly from a Hebrew etymology with no evident connection to the Greco-Egyptian ritual. Kent also says in the appendix of his study, while citing Karl Preisendanz, that the Egyptian god Set (Seth) was identified with a headless demon whose eyes were placed on his shoulders. Kent also suggests that the name given to the Headless One, Osoronophris, which is the name of a form or epithet of Osiris, identified Osiris with Set, his arch enemy, while at the same time asserting that Osiris and Set were both identified with a larger solar-pantheistic god and thus unified. Such a proposition is obviously fascinating, but I am unable to find any evidence to support this unity being associated with Osoronophris.

I am ultimately not inclined to agree that the Akephalos depicted in the Greek Magical Papyri is supposed to be Set, because the evidence for such a connection, as far as I can see, seems to be weak or lacking. In fact, it seems to me that the Akephalos has a stronger connection to Osiris than to his murderer. In fact, the Akephalos has been suggested by Ronaldo G. Gurgel Pereira to be a solar form of Osiris. In the Egyptian Book of Caverns, the dismembered Osiris’ missing head is the sun, and the other parts of his body are knitted into various parts of the underworld, or the head had a desire to be knitted onto the body in the underworld. In the same text, the solar scarab Khepri, as the regenerating or reborn sun, is called “attached of head”, implying the regeneration and reassembly of the body of Osiris. There is also an amuletic text from the time of the 25th Dynasty which describes Osiris as a “headless body”, “the mummy without a face”. The image of headlessness was apparently interpreted as a representation of formlessness, possibly connected to solar rebirth. That being said, I won’t dismiss the idea that Set was also represented as a headless god. More important, in any case, is the connotation of headlessness. According to J. C. Darnell, in The Engimatic Netherworld Texts of Solar-Osirian Unity, the headlessness of Osiris as Akephalos is not simply a result of Osiris being dismembered by Set, but instead represented the magical power of a solar god. In fact, the Akephalos represents a profound exception to the traditionally negative significance of headlessness in Egyptian symbolism. In this setting, it wasn’t simply the headlessness of the Akephalos that denoted his power, but rather the implication that his missing head was actually an invisible sun. The very headlessness of the Headless God simply heightened the presence of an unseen sun, and in this sense it may function as a kind of apophatic symbolism. There is also a papyrus from Deir el-Medina in which Akephalos or Osiris is alluded to as “the flaming one, the mummy without a face”. Osiris Akephalos is thus understood as the mummiform portion of the unified Ra-Osiris, the underworld form of the sun or Ra – in a sense, perhaps, the fiery (“flaming”) ruler of the underworld. Certainly a solar god in any case, a point not irrelevant to the solar discourse of Bataille’s mystical philosophy.

In fact, Bataille already associated headlessness with the sun by interpreting the headless deity as a solar image in his essay Rotten Sun (1930). There, Bataille argued that the sun has been mythologically represented as a man slashing his own throat, and/or an anthropomorphic being that has been deprived of its head. A similar association is also found in Base Materialism and Gnosticism (1930). In that essay, Bataille refers to the severed ass’ head as an acephalic personification of the sun, and thus one of the most virulent representations of base materialism (or what Nick Land used to call “libidinal materialism”). The head of an ass was, in ancient antiquity, interpreted as the head of the god Seth Typhon, who was sometimes associated with the sun, at least according to Plutarch. But, in this sense, the only thing that the Headless God definitely has in common with the Acephalic Man is the sun. The acephalic quality for Bataille takes on a much larger theme represented by the ecstatic creative-destructive solar flow that pervades the whole of Bataille’s writing, and is clearly evident in his presentation of both the Acephalic Man and the Ubermensch.

S. C. Hickman makes an important observation about the Akephalos in his article “Georges Bataille: The Excremental Vision as Solar Ecstasy“. In it, he notes that in Rodolphe Gasche’s book, Georges Bataille: Phenomenology and Phantasmology, there is a discussion of Friedrich Schelling’s research on the Sabians, whose religion he says involved a blind, acephalous god. The suprahistorical principle of this Sabianism is, according to Gasche and Schelling, an unmythological and unhistorical time. It is also said to consist of the fragmentation and tearing apart of the “real” principle, a principle of fear, represented in half-human and half-animal forms, through the violent unmanning of things by the self-asserting spiritual principle. The god of the spiritual principle cannot emerge without the death of the “real” god in violent struggle. This unmanning, for Gasche and Schelling, corresponds to the unmanning and downfall of the ruling, upright-standing gods. It is difficult, however, to find much of what Gasche is talking about. That said, there is a Tantric Hindu myth, which David Lorenzen recounts in his book The Kāpālikas and Kālāmukhas: Two Lost Śaivite Sects, that may present a narrative where the decapitation of the upright-standing gods is connected to a premise of salvific or liberatory detachment and to the antinomian rejection of traditional morality and dominant religious narratives.

In a text called the Goraksa-siddhanta-samgraha, whose authorship is attributed to the Kāpālika sect, the god Shiva appears as Ugra-Bhairava, a wrathful form of Shiva Bhairava who wears the garb of a Kāpālika and challenges the doctrine of the Advaita Vedanta school as propounded by Adi Shankara. Meanwhile, in the Kāpālika origin myth, the twenty-four avatars of the god Vishnu became arrogant and hubristic, and commit many outrages and crimes while wreaking havoc and suffering upon the earth. This angers the god Natha (Shiva), who incarnates as twenty-four Kāpālikas (skull-bearers) to fight the avatars of Vishnu, cut their heads off, and carry their skulls in their hands. After this, the avatars of Vishnu lose their hubris, and thus Natha (Shiva) replaces their heads and restores their life. Thus, the avatars of Vishnu are unmanned from the illusions that cause them to oppress the world, their authority is violently destroyed, and this violent detachment ultimately leads them to enlightenment and to their rebirth.

It remains very difficult to find other deities who are actually supposed to be headless. The one that springs to my mind immediately is Chinnamasta, the self-decapitating Tantric Hindu goddess. In Tibet, this goddess is called Chinnamunda, a self-decapitating form of the Vajrayana Buddhist deity Vajrayogini. Another curious headless god is the Chinese deity Xingtian, who fought against Huang Di for supremacy and lost his head but still continues to fight despite being decapitated. But let’s stick to Chinnamasta, because her cult is loaded with significance with respect to Bataillean headlessness.

For one thing, the cult of Chinnamasta is loaded with sexual charge, with Chinnamasta herself being depicted nude, standing or seated atop a divine couple of love deities – Kama and his wife Rati – joined in sexual intercourse. This, of course, is often said to signify sexual dominance and control over sexual desires, but Chinnamasta herself just as well could be said to signify raw sexual power, and the involvement of sexuality and sexual intercourse in the greater mystery represented by Chinnamasta. That said, some Tantric texts suggest that worshipping Chinnamasta involves having sex with a woman who is not your wife. For another thing, Chinnamasta is frequently depicting standing or seated in the centre of the disk of the sun. This may reflect a solar nature, also suggested to be connected to her (sometimes) red skin or complexion and association with the navel. Still another thing is her dark and fierce nature: her various names point her being served by ghosts and drinking human blood, she is pleased by flesh, blood, and meat, and worshipped by body, hair, and fearsome mantras, and she enjoys more than anything the dissolution of the world. Her proposed lineage is also fascinating.

According to David Kinsley in his book Tantric Visions of the Divine Feminine: The Ten Mahāvidyās, there are several examples of nude Indian goddesses that are depicted with prominently displayed genitalia and as being either headless or simply faceless. This headlessness may not share the force or significance of Chinnamasta’s self-decapitation, but it may still signify self-destruction mixed with sexuality. Another suggestion is that Chinnamasta’s cult was influenced by that of Kotavi, a fierce and wild goddess of war who was also counted as one of the Asuras or one of the Matrika (Mothers). Or there is Korravi, a fearsome hunting goddess who received blood sacrifices and was believed to grant victory in the battlefield. Most importantly, Kinsley notes, Chinnamasta represents the inextricable reality that all life feeds on other life, and thus that life feeds on death, in order to be sustained or come into existence, and thus life necessitates death. Sex is a part of this in that sex ultimately produces more life, which then decays and dies to feed more life. The blood flowing from her severed head conveys the loss of the life force, which then nourishes her devotees, and presumably also herself since she drinks her own blood. Her sexuality and her love of dissolution are linked together in a way that connects ultimately to the death drive, which in this meaning really signifies the self-perpetuation of life or the continuity of existence.

In a sense, Chinnamasta represents, in her own, unmanning. The act of severing her own head signifies not only the violent nourishing and replenishing of life, but also, traditionally, the overcoming of sexual desire through the practice of yoga, and the sacrifice or surrender of the self for the benefit of others. Awfully altruistic, though certainly profound. On the other hand, some images of Chinnamasta, in which she stands upon Shiva, she is not suppressing or overcoming Shiva, and perhaps not suppressing or overcoming sexual desire. Instead, she energizes Shiva and sexual desire. Still, the self-decapitation also had a more symbolic and philosophical significance: the head represents what Bataille understands as our immediate sense of discontinuous identity, and thus, in Hindu terms, our attachment to ignorance and illusion, so to remove the head represents the removal of illusion from one’s consciousness. I find the idea that it communicates a kind of self-perpetuating death drive to be more profound than the military ethos of self-sacrifice traditionally attributed to her, and in a way it really illustrates the coincidence between life, sex, and death.

There is something wonderfully Bataillean and Sadean about Chinnamasta’s whole symbolism. The sexual vitality of Chinnamasta is explicitly connected to her destructive nature, in the sense that this destruction is what forms the core of life. That Kinsley says her image jolts the viewer into the truth of the coincidence and interdependence of sex, death, and life almost seems to suggest a truth that blinds people with its violent sight, like the sun. Chinnamasta in this sense speaks somewhat like De Sade’s libertines do, in that they justify their actions by positing a law or system of nature in which destruction plays a central role: destruction is a part of nature, just as much as creation is, and not only that destruction is actually necessary to allow Nature to create and rearrange matter, and so virtue and vice are equally part of nature. The human body may become a swarm of centipedes after it dies and it makes no difference to nature. And in her paradoxical nature, everything violent and mortifying about Chinnamasta supports life, peace, and renewal, basically everything we consider to be good. Through it all. Chinnamasta embodies a kind of unmanning that brings human consciousness away from its own illusions about the world and itself, and towards a truth that liberates it, or at least violently releases it from its sleep. The unmanning of the self, the escape of “Man” from his “head”.

In the final analysis, I would say that it is only the solar image of headlessness that connects Bataille’s Acephalic Man with the Headless God. And yet, there is not such a gulf between the significances of these two figures. The Death of God is after all a source of life, much like the headlessness of Osiris is the presence of the sun. It is perhaps worth noting finally that the Headless God/Daimon in the Greek Magical Papyri could be seen as a theurgical object, in the sense that the original rite might have been performed to the effect that it culminated in the magician identifying with and “becoming” the headless divinity that they sought to invoke. Might one be able to speak of theurgical transformation into the sun? And thus every man and woman is a star by being a sun.